- Set your retirement goals and determine how much savings you need with this accessible retirement financial planner template. Enter your age, salary, savings, and investment return information, as well as desired retirement age and income, and the retirement planning template will calculate and chart the required earnings and savings each year to achieve your goals.

- The Bond Calculator can be used to calculate Bond Price and to determine the Yield-to-Maturity and Yield-to-Call on Bonds. Bond Price Field - The Price of the bond is calculated or entered in this field. Enter amount in negative value.

- I Savings Bond Calculator

- Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free

- Calculator

- Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free Online

- Savings Bond Calculator Download

- Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free Pdf

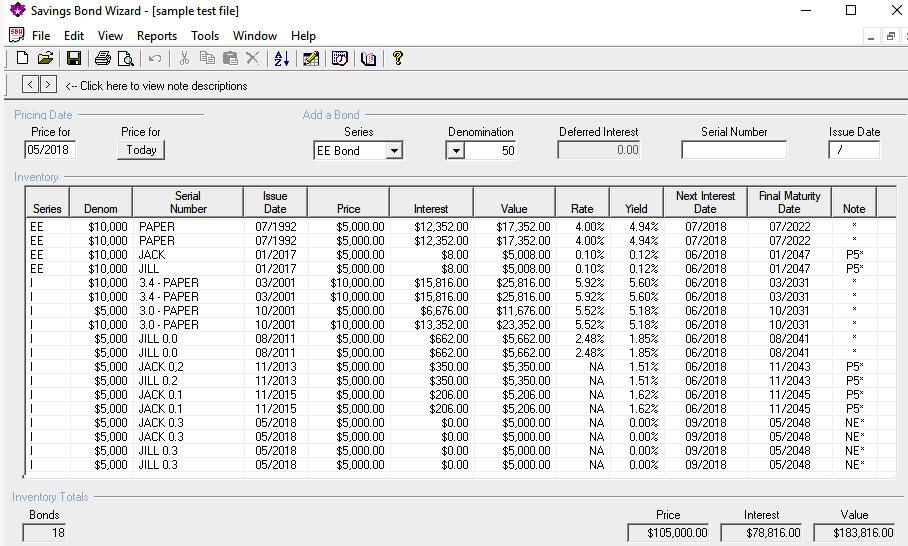

The Savings Bond Calculator WILL: Calculate the value of a paper bond based on the series, denomination, and issue date entered. (To calculate a value, you don't need to enter a serial number. However, if you plan to save an inventory of bonds, you may want to enter serial numbers.) Store savings bond information you enter so you can view or update it later. In 2019, Freddie Mac issued a record-breaking $78 billion in apartment financing, including $23.1 billion in “green” apartment loans. In addition to standard apartment loans, both Fannie and Freddie also offer financing for senior living and healthcare properties, including nursing homes. Get a free Apartment Loan Quote.

Purchasing U.S. savings bonds can be one of the safest ways to earn money on your savings, as a savings bond’s value is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. They can also offer tax advantages over similar products, such as a savings account or certificate of deposit (CD).

Although you might not earn a lot of interest, the guaranteed return can make them an important part of some people’s portfolios. Learn more about how savings bonds work, how to calculate their value, and how to redeem.

How Savings Bonds Work

When you buy U.S. savings bonds, you’re lending the government money, and it will pay you back with interest. How much interest you’ll earn depends on the type of bond you have and how long you’ve held onto it.

Today, you can buy two types of U.S. savings bonds—Series EE and Series I.

- Series EE savings bonds have a fixed interest rate (Series EE bonds issued before May 2005 may have a variable rate). Starting with a $25 bond, you can buy up to $10,000 per year online at TreasuryDirect.gov. Interest gets added to the bond monthly, and the government guarantees that the bond will double in value after 20 years. After 30 years, EE savings bonds mature and stop accruing interest.

- Series I savings bonds have a fixed interest rate plus a variable rate based on inflation, which can change every six months. Although deflation could lead to a negative variable rate, the lowest your bond’s rate will go is 0%. You can buy Series I savings bonds online starting at $25 or purchase paper bonds starting at $50 with your federal tax return, up to $10,000 and $5,000 per year, respectively. The government doesn’t guarantee earnings, but interest can accrue for up to 30 years.

While these are the only types of savings bonds you can buy today, there are other types that you may have bought or been given in the past. You can use a savings bond calculator to find out how much they’re worth and determine if you want to redeem them now or wait.

Figuring Out How Much Your Savings Bond Is Worth

Savings bonds don’t provide a steady flow of income like a dividend-paying stock. Instead, accrued interest is added to the savings bond’s value, which you’ll receive when you redeem the bond.

With both Series EE and Series I bonds, the interest accrues monthly and compounds twice a year. You can use a calculator — like this savings bond calculator provided by TreasuryDirect — to determine the value of your savings bonds. You’ll need some information to get started:

- Series type

- Denomination

- Bond serial number

- Issue date

You must hold onto Series EE and I bonds for at least 12 months before you can cash out. Additionally, if you cash out one of the bonds before five years, you’ll lose three months’ worth of interest as a penalty.

Additionally, if you have Series EE bonds, don’t forget about the guaranteed doubling of value after 20 years. Although the interest rate may be low — it’s only 0.10% for bonds issued from May to October 2020 — you’ll still earn an effective rate of 3.5% if you hold the bonds for 20 years.

How to Cash in a Savings Bond

You can cash in electronic bonds online at TreasuryDirect.gov. Or, if you have paper bonds, you can cash in at a local financial institution, such as a bank or credit union.

Savings bonds don’t expire, but Series EE and I bonds mature after 30 years, which means bonds issued before 1990 won’t accrue any more interest and there’s little reason to hold onto them. Sometimes, this may happen without you realizing it, such as if someone gave you a bond when you were a child.

As of the end of 2019, more than $26 billion dollars worth of unredeemed savings bonds had matured and stopped earning interest. You can use Treasury Hunt to search for bonds based on your tax identification number and state of residence.

When you cash in a bond, you’ll be issued a 1099-INT with a record of earned interest. Although you don’t have to pay local or state taxes on the earnings, you may need to pay federal income taxes.

You may also want to cash in a bond even if it hasn’t matured yet if you have a good use for the money. For example, eligible bondholders can avoid paying federal income taxes if they cash in and use the funds for qualified higher education expenses.

Or, you may want to cash in bonds if you need the money for living expenses during retirement or if you have a better investment opportunity elsewhere.

Bottom line: If you don’t need the money now and the interest is still being added, you might want to stow savings bonds in your safe deposit box until they fully mature. But if those bonds you got from as birthday gifts from your well-meaning extended family have matured, cash in and move those earnings to a higher interest investment.

Take control of your finances with Quicken.

Try Quicken for 30 days risk-free!

Are you a student? Did you know that Amazon is offering 6 months of Amazon Prime - free two-day shipping, free movies, and other benefits - to students?

Click here to learn more

One of the key variables in choosing any investment is the expected rate of return. We try to find assets that have the best combination of risk and return. In this section we will see how to calculate the rate of return on a bond investment. If you are comfortable using the built-in time value functions, then this will be a simple task. If not, then you should first work through my Microsoft Excel as a Financial Calculator tutorials.

Please note that this tutorial works for all versions of Excel. Furthermore, the functions presented here should also work in other spreadsheets (such as Open Office Calc).

I Savings Bond Calculator

You can download a spreadsheet that accompanies this tutorial, or create your own as you work through it. Since we will use the same example as in my tutorial on calculating bond values using Microsoft Excel, the spreadsheet is the same.

The expected rate of return on a bond can be described using any (or all) of three measures:

- Current Yield

- Yield to Maturity (also known as the redemption yield)

- Yield to Call

We will discuss each of these in turn below. In the bond valuation tutorial, we used an example bond that we will use again here. The bond has a face value of $1,000, a coupon rate of 8% per year paid semiannually, and three years to maturity. We found that the current value of the bond is $961.63. For the sake of simplicity, we will assume that the current market price of the bond is the same as the value. (You should be aware that intrinsic value and market price are different, though related, concepts.)

If you haven't downloaded the example spreadsheet, create a new workbook and enter the data as shown in the picture below:

The Current Yield

The current yield is a measure of the income provided by the bond as a percentage of the current price:

[{rm{Current,Yield}} = frac{{{rm{Annual,Interest}}}}{{{rm{Clean,Price,of,Bond}}}}]

There is no built-in function to calculate the current yield, so you must use this formula. For the example bond, enter the following formula into B13:

=(B3*B2)/B10

The current yield is 8.32%. Note that the current yield only takes into account the expected interest payments. It completely ignores expected price changes (capital gains or losses). Therefore, it is a useful return measure primarily for those who are most concerned with earning income from their portfolio. It is not a good measure of return for those looking for capital gains. Furthermore, the current yield is a useless statistic for zero-coupon bonds.

The Yield to Maturity on a Payment Date

Unlike the current yield, the yield to maturity (YTM) measures both current income and expected capital gains or losses. The YTM is the internal rate of return of the bond, so it measures the expected compound average annual rate of return if the bond is purchased at the current market price and is held to maturity. In this section, the calculations will only work on a coupon payment date. If you wish, you can jump ahead to see how to use the Yield() function to calculate the YTM on any date.

In the case of our example bond, the current yield understates the total expected return for the bond. As we saw in the bond valuation tutorial, bonds selling at a discount to their face value must increase in price as the maturity date approaches. The YTM takes into account both the interest income and this capital gain over the life of the bond.

There is no formula that can be used to calculate the exact yield to maturity for a bond (except for trivial cases). Instead, the calculation must be done on a trial-and-error basis. This can be tedious to do by hand. Fortunately, the Rate() function in Excel can do the calculation quite easily. Technically, you could also use the IRR() function, but there is no need to do that when the Rate() function is easier and will give the same answer.

To calculate the YTM (in B14), enter the following formula:

=RATE(B5*B8,B3/B8*B2,-B10,B2)

You should find that the YTM is 4.75%.

But wait a minute! That just doesn't make any sense. We know that the bond carries a coupon rate of 8% per year, and the bond is selling for less than its face value. Therefore, we know that the YTM must be greater than 8% per year. You need to remember that the bond pays interest semiannually, and we entered Nper as the number of semiannual periods (6) and Pmt as the semiannual payment amount (40). So, when you solve for the Rate the answer is a semiannual yield. Since the YTM is always stated as an annual rate, we need to double this answer. In this case, then, the YTM is 9.50% per year. Change your formula in B14 to:

=RATE(B5*B8,B3/B8*B2,-B10,B2)*B8

So, always remember to adjust the answer you get from Rate() back to an annual YTM by multiplying by the number of payment periods per year.

The Yield to Call on a Payment Date

Many bonds (but certainly not all), whether Treasury bonds, corporate bonds, or municipal bonds are callable. That is, the issuer has the right to force the redemption of the bonds before they mature. This is similar to the way that a homeowner might choose to refinance (call) a mortgage when interest rates decline. In this section, the calculations will only work on a coupon payment date. If you wish, you can jump ahead to see how to use the Yield() function to calculate the YTC on any date.

Given a choice of callable or otherwise equivalent non-callable bonds, investors would choose the non-callable bonds because they offer more certainty and potentially higher returns if interest rates decline. Therefore, bond issuers usually offer a sweetener, in the form of a call premium, to make callable bonds more attractive to investors. A call premium is an extra amount in excess of the face value that must be paid in the event that the bond is called before maturity.

The picture below is a screen shot (from the FINRA TRACE Web site on 8/17/2007) of the detailed information on a bond issued by Union Electric Company. Notice that the call schedule shows that the bond is callable once per year, and that the call premium declines as each call date passes without a call. If the bond is called after 12/15/2015 then it will be called at its face value (no call premium).

It should be obvious that if the bond is called then the investor's rate of return will be different than the promised YTM. That is why we calculate the yield to call (YTC) for callable bonds.

The yield to call is identical, in concept, to the yield to maturity, except that we assume that the bond will be called at the next call date, and we add the call premium to the face value. Let's return to our example:

Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free

Assume that the bond may be called in one year with a call premium of 3% of the face value. What is the YTC for the bond?

I have already entered this additional information into the spreadsheet pictured above. The formula in B15 will be the same as for the YTM, except that we need to use 2 periods for NPer, and the FV will include the 3% call premium:

=RATE(B6*B8,B3/B8*B2,-B10,B2*(1+B7))*B8

Remember that we are multiplying the result of the Rate() function by the payment frequency (B8) because otherwise we would get a semiannual YTC. Note that the yield to call on this bond is 15.17% per year.

Now, ask yourself which is more advantageous to the issuer: 1) Continuing to pay interest at a yield of 9.50% per year; or 2) Call the bond and pay an annual rate of 15.17%? Obviously, it doesn't make sense to expect that the bond will be called as of now since it is cheaper for the company to pay the current interest rate.

The YTM and YTC Between Coupon Payment Dates

As noted above, a major shortcoming of the Rate() function is that it assumes that the cash flows are equally distributed over time (say, every 6 months). However, bonds only pay interest twice a year, so there are only 2 days per year that the Rate() function will give the correct answer. On any other date, you need to use the Yield() function. Note that this function (as was the case with the Price() function in the bond valuation tutorial) is built into Excel 2007. However, if you are using Excel 2003 or earlier, you need to make sure that you have the Analysis ToolPak add-in installed and enabled (go to Tools » Add-ins and check the box next to Analysis ToolPak).

The Yield function is defined as:

YIELD(settlement,maturity,rate,pr,redemption,frequency,basis)

where settlement is the date that you take ownership (typically 3 business days after the trade date), maturity is the maturity date, rate is the annual coupon rate, pr is the current market price as a percentage of the face value, redemption is the amount that will be paid by the issuer at maturity as a percentage of the face value, frequency is the number of coupon payments per year, and basis is the day count basis to use. Note that the dates must be valid Excel dates, but they can be formatted any way you wish. Also, both pr and redemption are percentages entered in decimal form. That is, 96 indicates 96% so don't enter 0.96 even if you format it as a percentage.

Our worksheet needs a little more information to use the Yield() function, so set up a new worksheet that looks like the one in the picture below:

Note that I've had to add exact dates for the settlement date and the maturity date, rather than just entering a number of years as we did before. Also, since industry practice (which the Yield() function uses) is to quote prices as a percentage of the face value, I have added 100 for the redemption value in B3. Finally, I have added a row (B11) to specify the day count basis. In this case, we are using the 30/360 day count methodology, which Excel specifies as 0.

With that additional information, using the Yield() function to calculate the yield to maturity on any date is simple. Insert the following function into B18:

Calculator

=YIELD(B6,B7,B4,B13,B3,B10,B11)

and you will find that the YTM is 9.50%. Notice that we didn't need to make any adjustments to account for the semiannual payments. The Yield() function takes annual arguments, and uses the Frequency argument to adjust them automatically. It also returns an annualized answer.

Calculating the yield to call is done in the same way, except that we need to add the call premium to the redemption value, and use the next call date in place of the maturity date. Enter the following function into B19:

=YIELD(B6,B8,B4,B13,B3*(1+B9),B10,B11)

Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free Online

You should find that the YTC is 15.17%.

As noted, the nice thing about the Yield() function is that it works correctly on any day of the year. To see this, change the settlement date to 12/15/2007 (halfway through the current coupon period). You should find that the YTM is still 9.50%, but the YTC is now 17.14%.

Savings Bond Calculator Download

Make-Whole Call Provisions

The above discussion of callable bonds assumes the old-fashioned type of call. However, for the last 15 years or so, corporations have typically used a 'make-whole' type of call. To learn about those, please see my tutorial for make-whole call provisions.

Savings Bond Calculator For Mac Free Pdf

I hope that you have found this tutorial to be helpful. If you wish, you can return to my Excel TVM tutorials, or view my Excel Bond Valuation tutorial.